Industry, Inventiveness, and Ambition:

The Art of the Staffordshire Figure

By Adele Kenny

Reprinted with the kind permission of The Antiquer: Fine Art & Antiques, April 2005.

Copyright © 2005. All rights reserved.

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, voyages of discovery from Western Europe into the New World brought about increased trade and generated the beginnings of European market economies. Establishment of the Bank of England in 1694 and the replacement of England’s “merchant adventurers” by “capitalistic entrepreneurs” prepared Britain for the Age of Industry. The manifold effects of the Industrial Revolution included advancements in technologies, improved transportation systems, the development of steam engines, and the swelling of urban centers. All of these contributed to the advent of a factory system, large-scale machine-based production, and amplified economic specialization that elevated England to the international vanguard and ultimate designation as the first industrial nation.

Industrialization became the bedrock of dramatic changes in social and economic structure. As machinery monstered Britain into the Industrial Age, a larger labor force was needed, and as mechanization gave rise to the working class, it also powered an increasing middle class that required greater quantities of affordable better-made goods. In the largely agrarian region of North Staffordshire, pottery had been made as early as Roman times. Until the mid-eighteenth century, functional pottery was made in farmyard potbanks where farmer potters literally milked cows in the shadows of their kilns. Beginning around 1740, decorative figures were added to the potters’ repertoire, and a new industry began to emerge. Figures produced from about 1740 included saltglazed stoneware models of small animals, people, and curious women (designed in the shape of bells), “pew groups” (depicting people seated on high-backed benches or settles), and “arbor groups” (characterized by arbor-like settings). Most early figures were naïvely rendered and, although machine manufacture was on the rise, every figure of this period was made by hand-construction, unlike later figures that were produced through mold technologies.

Although “pottery plagiarism” was rampant and various pottery-making secrets were stolen, sold, or shared (often through intermarriages among potting families), the spirit of change and progress led many potters to experimentation that raised the Staffordshire figure from its folk art roots into higher realms of imagination and individuality. As figure making found increased favor among consumers, the potters began to explore the possibilities of innovative coloring and glazing techniques. Quality improved, and subject matter widened. The introduction of cream-colored earthenwares and colored oxide decoration led to a new class of figures that included a range of huntsmen, gamekeepers, animals, women with panniered skirts, high-based equestrians, and military personnel.

Staffordshire figures were rarely marked by their potters through all periods of production; however, some are known to today’s collectors through tradition and primary sources. John Astbury (1688-1743) and Thomas Whieldon (1719-95) were among the luminaries of their time, and what is known of them derives from both tradition and primary sources. Astbury is said to have gained his technical knowledge from the Elers brothers who came to England from Holland, presumably with the court of William of Orange. The Elers brothers guarded their pottery-making secrets so zealously that, according to tradition, they only hired employees who were “idiots.” Although unlikely, tradition also holds that at the age of about twelve Astbury posed as simple-minded, gained access to the brothers’ formulas, and used what he learned to set up his own pottery. Small figures attributed to Astbury were crudely modeled but display significant originality. Most portray animals and people made through combined processes of hand modeling and press molding, highlighted with slip-crafted details, and colored through use of metallic oxides. Because Astbury never used a potter’s mark, no figures can be positively attributed to him, and “Astbury-type” is the generic term used to identify this class of figures. Thomas Whieldon is possibly the most celebrated potter of his time. He is associated with early cream-colored wares, black ware with gilt decoration, colored oxide decoration, mottled tortoiseshell glazes, and agate ware items. Excavations at his Fenton Vivian site have revealed various figures and fragments of musicians, soldiers, gamekeepers, and other rural subjects. Similar unmarked wares of the same period are broadly termed “Whieldon-type” by today’s collectors. Many future greats of the Staffordshire potteries worked with Whieldon; his most famous partner was Josiah Wedgwood, who worked with Whieldon from 1754 until 1759. Others included members of the Spode family and Aaron Wood.

The peasant potters of Staffordshire were destined for undreamed of heights. As figure making grew in popularity, changes occurred within the potteries. Experimentation in modeling, decorating, and glazing was ongoing, but most noteworthy was the move to wholly mold-produced figures. Also important was a shift in subject matter from exclusively English themes to subject matter prompted by a wider range of sources. As the potters’ scope expanded, specialization in any one type of figure ceased.

Figures produced at the end of the eighteenth century marked a drastic change from mid-century styles and subjects. The Wood family of potters (including Ralph I, John, Ralph II, Ralph III, John II, Aaron, and Enoch) set the standards of excellence for Staffordshire’s figure industry. The Woods are best known for superior modeling and for distinctive use of colored glazes and overglaze enamels. The developments of pearlware and enameled decoration represented important breakthroughs in pottery technology.

Enoch Wood, acknowledged as the most talented modeler of all times, joined the pottery in 1784; the naturalism of his figures, finished in color-glazed and enameled decoration, has never been surpassed, and he is known as “The Father of the Potteries.” While many potters copied Enoch Wood’s style, an innovation concurrent with Enoch’s figure-making triumphs was a class of enameled figures known today as Pratt Wares (a collector’s term that is not supported by proof that the Pratt family of potters ever produced figures). So-called “Pratt Wares” are characterized by white or pale cream bodies and decoration in a limited range of blue, green, yellow, orange, brown, and black colored oxides. Their quality varies from crude to well executed, and, most likely, a number of potters worked in the style.

Staffordshire’s early nineteenth century potters were keen businessmen. Driven by the multiple effects of the Industrial Revolution to bridge the crevasse between art and industry, their communal goal was to provide decorative figures that could rival more expensive porcelains for a fraction of the cost, thus satisfying the requirements of the middle and moneyed working classes that sought self and social betterment through financial success, education, or possession of the trappings that polished a veneer of sophistication and upward mobility.

During the first decades of the nineteenth century, the potters began to focus on their immediate world for inspiration. “Isolated” figures of individuals or groups bowed to the genesis of figures contained in microenvironments that included trees, animals, and buildings. One class of figure that emerged between 1810 and 1820 was the “bocage” figure (from the French meaning “woodland”) that mimicked leafy tree forms encrusted with small florets that porcelain makers like Chelsea, Bow, and Derby incorporated into their figures as a means of support against collapse in the kilns. Most earthenware bocage figures lacked the refined elegance of porcelain figures in the same genre; however, they were distinguished by naïve charm and bright colors. Geared to suit the interests of the middle class market, bocage figures adopted Biblical themes, classical characters, shepherds, gardeners, archers, musicians, “Dandies,” traveling menageries, country-inspired motifs, and anecdotal pieces with political and satirical intent. Among the bocage figure potters was John Walton, whose signed figures gave all bocage figures and groups the common classification of “Walton School.” Producing bocage figures over a period of about twenty-five years, Walton School potters included Ralph Salt, Charles Tittensor, Edge & Grocott, and numerous others.

Of all the innovations in early nineteenth century Staffordshire, table base groups – set on platforms that resemble tables with four or six squat legs and bracket-type feet – were the most extraordinary. While many Staffordshire figures stand on bases, the table base is unique and provides a kind of “stage” on which slice-of-life dramas have been seemingly stopped in action. Possessing a bold and earthy charisma, these groups were “muscular” in subject and style, crudely modeled, and made of pearl glazed earthenware decorated with overglaze enamels; their construction required multiple molds and complex assemblies. Many were titled, some in scalloped “tabs” centered between the front legs of the bases. Suggesting a Madame Tussaud-like chamber of horrors aspect, many of the most striking depict grisly subjects that would have captured the buying public’s interest, including bull baiting, the death of Lieutenant Hector Monroe, and the 1828 Red Barn Corder/Marten murder. Two of the most elaborate table base groups represent the entrances to Polito and Wombwell’s menageries and were produced in several variants. In other table base groups, domestic life was robustly lampooned as in “Ale Bench” and “Tee-Total” (a drunken man suffers his wife’s anger in the first and a sober man enjoys household harmony in the second). The same sort of humor underlies figures like “Who Shall Wear the Breeches · Conquer and Die” (which depicts a man and woman tugging at a pair of trousers in front of their fireplace). Wit aside, such groups were an assertion of the potters’ new responsibility as social commentators. Along with subjects like the “Reading Maid,” “Romulus and Remus,” and a somewhat explicit “Grecian and Daughter,” the nineteenth century preoccupation with religion was addressed in table base figures that included a christening group, “Christ’s Agony,” “Peter Raising the Lame Man,” and “Prepare to Meet Thy God.”

The question of who made the table base figures and groups remains an unsolved mystery. These figures were not abundantly produced and, although the feet were modeled in several styles, many believe that table bases were made by a single potter. For some time, attribution to Obadiah Sherratt was considered correct. However, the only known pieces signed by Sherratt are two earthenware frog mugs, and traditional Sherratt attribution has yet to be substantiated by documentary or archaeological evidence. Whoever the potter was, his work was revolutionary – a stunning perspective on the realities of early nineteenth century British life.

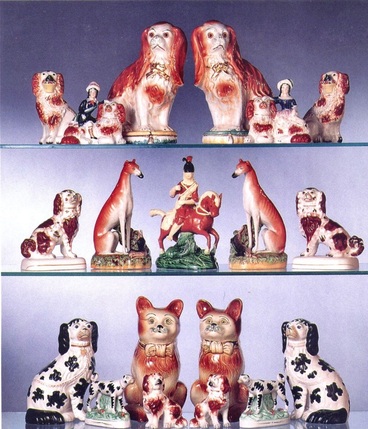

By the time Victoria became queen, Staffordshire figures had taken on the role of social barometer and historian. Continuing improvements in transportation systems, better communication technologies, wider use of mass production techniques, and increased literacy all buttressed the pervasive need within the middle and working classes to exhibit a façade of affluence and progressive inclination. As Britain continued her ascent to international prominence, the phenomenon of the portrait figure joined ranks with paired Spaniel and other animal models, pastoral motifs, and even buildings – a diverse assortment of subjects drawn from contemporary life and popular art and culture. Portrait figures brought high interest persons into the homes of average British citizens, and offered their owners an opportunity to “participate” in current events by placing figures of newsworthy personalities on their mantelpieces.

A few portrait figures were made before the Victorian Era, but Victorian portrait figure production was a direct response to the budding cult of the celebrity. During the 1840s, subjects included members of the royal family and their continental relatives and counterparts, usually produced in complementary pairs. By the time of the Crimean War, soldiers, sailors, allied war leaders, and even the sites of military engagements became figure subjects. Potters found inspiration in the media of the time (newspapers, broadsheets, magazines, books, music sheet covers, and theater programs, which were made more accessible by improvements in printing and lithography), and produced figures in a comprehensive assortment of heroes, heroines, criminals, children, religious leaders, Biblical personalities, writers, explorers, and entertainers.

Although figures were hand made and individually decorated, they were created through “production line” methods, as commercial viability was paramount. Workers were never lacking as a result of the social dislocation wrought by the Industrial Revolution and, in many potteries, the workers’ welfare was largely ignored. Pottery workers were prone to consumption, asthma, rheumatism, and other diseases – the results of working with toxic materials, dust filled environments, overheated rooms, exposure to cold in winter, lack of exercise, and poor nutrition. Many of the workers spent up to sixteen hours a day in small rooms that were damp, dark, dirty, and badly ventilated. Child labor was cheap, and regardless of the Factory Act of 1844, employment of young children was commonplace. By 1851 nearly forty thousand persons were involved in figure making and another six thousand were employed in marketing. Staffordshire figures were in such high demand among consumers that they were produced in the hundreds of thousands, and the “flatback” came into vogue. Flatback figures were decorated only in the front with sparsely modeled and undecorated flat backs designed for placement on mantles – an innovation that was almost modernist and not done before, after, or anywhere else in the world. Flatbacks saved production time and expense and, clearly, the potters’ interests had become primarily fiscal.

Despite introduction of the commercially successful flatback, one mid-nineteenth century potter, Thomas Parr, maintained a high standard of artistic integrity and produced figures that were finely modeled in the round with superbly executed decoration. Parr, Staffordshire’s William Morris, pulled figure making from the quicksand of commercialism, and his work, a kind of retroactive innovation, fit into the broader spectrum of the arts, returning truth to medium and ennobling craftsmanship. But Parr was singular and, although the figure-making industry remained strong through all of Victoria’s long reign (1837-1901), quality declined substantially by the 1880s. Ubiquitous Spaniels, portraits, and nearly all types of figures took on a “formula” look, and once-vibrant colors were replaced by simple white and gilt decoration. By the outset of World War I, figure making had become passé.

The heyday of Staffordshire figures corresponded to a time of adamant vision and unparalleled innovation in industry, technology, aesthetics, beliefs, and ideals. Set against the backdrop of a time held in the thrall of uncompromising change and unmitigated contrasts, the potters encapsulated artistic, technological, moral, and social transformation in their product.

Bringing a folk art-based industry to the masses, Staffordshire figures reflected the issues of middle England, a population wedged between the abject poverty of factory laborers and the extreme wealth of the upper classes – a population that strove for betterment but was not immune to worldly excess and self-deception. As factories began pouring the smoke that is now called pollution into the air, as steam engines thrust machinery and travel into the future, as huge numbers of rural dwellers left the countryside to seek employment and better lives amid the squalor of urban centers, Staffordshire figures bore witness to the aspirations, interests, and dreams of a people who lived on the brink of the “modern” world.