Pioneer Photography in America:

The Daguerreotype

By Adele Kenny

Reprinted with the kind permission of The Antiquer.

Copyright © 2003. All rights reserved.

As early as the fourth century B.C., Chinese scholars wrote about the camera obscura: if a small hole is pierced in a piece of paper that is placed in the window of a dark room, an image of the outdoor view will be projected, inverted, onto the opposite wall. During the early 1800s, various individuals experimented with this concept and attempted to fix projected images on light-sensitive materials. In England, Thomas Wedgwood discovered in 1802 that silver salts would render paper or leather sensitive to light, and a few decades later, another Englishman, Henry Fox Talbot, produced a paper soaked in table salt and silver nitrate then washed in potassium iodide that became a negative from which he could make limitless positives by placing additional sensitized papers in contact with the negative and exposing them to light. In 1829, Frenchmen Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre and Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce collaborated in carrying out image-making experiments with the goal of creating an image from life through a reaction to light. After Niépce’s death in 1833, Daguerre continued to experiment, and on August 19, 1839, his photographic process was made public via the French government – an announcement that literally changed the world.

Named for its creator, the daguerreotype was made through a direct-positive process that created a detailed image on a sheet of copper that was plated with a thin coating of silver without the use of a negative. The silver plated copper plate was first cleaned until its surface resembled a mirror. The plate was then sensitized in a closed box over iodine until it took on a yellowish-rose color. The plate was next placed in a lightproof holder and transferred to the camera where a lens cap was removed and the exposure was started. After being exposed to light, the plate was developed over mercury until an image appeared. The image was fixed by immersion in a solution of sodium thiosulfate or salt before final toning with gold chloride. The earliest daguerreotypes required long exposure times that ranged from three to fifteen minutes – times quickly reduced through adjustments to the sensitization process and lens improvements.

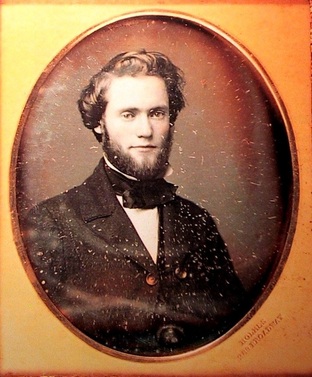

Because daguerreotypes were produced inside the camera, they are unique, one-of-a-kind, images. Copies were only possible through photographing an original image or through lithography or engraving and, often, daguerreotype portraits of important persons were reproduced by the latter means for publication in printed materials. Daguerreotypes are easily distinguished from other forms of pioneer, one-of-a-kind photographs like ambrotypes and tintypes because of their mirror-like appearance. Ambrotypes, produced slight later than daguerreotypes were less expensive to make by securing faint images on the backs of small glass plates. Although they looked like negatives, they were not, and each required a backing of black varnish, black-painted glass, or black fabric to be seen clearly. Tintypes were the last of the one-of-a kind early photographs. Like daguerreotypes, tintypes were produced on metal plates rather than on glass like ambrotypes. The metal used was iron, and the term “tintype” is a misnomer of uncertain origin. To make a tintype, a wet collodion process on black or brown enameled plates was used to produce positive images directly on the iron plates. Distinguished by dark surface coloration, tintypes achieved popularity over daguerreotypes and ambrotypes because they were cheaper to produce, less vulnerable to breakage or scratching, and not subject to oxidation. However, they lacked the daguerreotype’s refinement and came to be known as “the poor man’s daguerreotypes.” Made extensively in America, they were largely rejected abroad.

The daguerreotype process was introduced just two years after Victoria acceded to the British throne. Joining other post Industrial Revolution successes, Daguerre’s announcement was concurrent with advancements in various technologies, and photography, even in its infancy, took the western world by storm. Americans, in particular, adopted the process with astonishing enthusiasm. Pioneer American photographers progressed beyond Daguerre’s still life and architectural subjects into portrait photography even before accelerants were developed and, despite specially designed stands that helped the “sitter” remain still, many a stiff neck must have resulted from the long exposure times needed to make the first portrait images. Just prior to Daguerre’s announcement, he met with Samuel F. B. Morse in France where they shared ideas. When Morse returned to the United States, he became involved in image making along with Robert Cornelius of Philadelphia, John Johnson, and Alexander Wolcott (who invented a camera that shortened exposure time). In record time, photographers from all walks of life joined the image-making brigade as specialists and as itinerants (who combined various trades with side professions in daguerreotyping). A satellite industry in making cases to protect the delicate images developed at the same time and became highly competitive.

By 1851, stereographs, or stereo views, were made using the daguerreotype and ambrotype processes. These consisted of two views of the same image taken by cameras placed next to each other. Later, binocular cameras were used to produce images of photographic subjects on single negative plates. When developed, the paired images were viewed stereoscopically in specially designed cases to create a three-dimensional image.

Americans comprised the daguerreian vanguard, and by the mid-1850s, New York City had become the center of photographic activity. Specialist case makers grew in number, but many photographers doubled as case makers and photographic materials and apparatus suppliers. Traveling agents promoted the new industry and, before long, daguerreotypes were being made throughout the country. The Boston Daily Evening Transcript (December, 18, 1850) reported, “…American daguerreotypes are acknowledged to surpass either English or French.” And, in 1853, The Illustrated Family Christian Almanac for the United States contained the following entry, “Everyone is familiar with the daguerreotype, in which not only likenesses of persons, but images of all kinds of objects are transferred from the lens of the camera obscura, and permanently fixed on metallic plates.”

Today’s collectors seek all three pioneer photographic forms, but daguerreotypes are the most sought after. Average daguerreotypes of unidentified persons are the least highly valued and may be purchased for $35-$55. Daguerreotypes were made in a range of sizes; the largest (whole plate) are the most rare and costly. Because daguerreotypes were kept in cases made of die-engraved paper and leather or of plastic composition and novelty materials, they are often sold as case and image units: combined rare cases and rare images command the highest values. Cases and images by Matthew Brady, whose photographs of Civil War battle scenes were the first record of America at war, are among the highest priced, along with extremely rare views of the moon and identifiable places like Niagara Falls. Collectors compete for Civil War soldiers and scenes, portraits of important persons, Afro-Americans, American Indians, occupational portraits (especially those including “tools of the trade”), post mortem images, nudes, images of circus sideshow or deformed individuals, outdoor views, hand tinted images, and stereographs. Also uncommon and pricey are daguerreotype portraits of people holding daguerreotype cases or standing beside a table on which a daguerreotype case was placed.

It is hard to imagine, in today’s digital culture, the extent of the daguerreotype’s impact on the lives of everyday people whose likeness could be recorded for the first time with the accuracy of permanent mirrors. Perhaps these excerpts from a poem entitled, “Lines on a Daguerreotype,” (Boston Daily Evening Transcript, August 7, 1850) sum up the popular sentiment of the time as well as the feelings of twenty-first century collectors:

Delicate pencillings of imprisoned light!

Tracings imprinted with the finest care,

Revealing to the eye an image bright…

…’tis strange, indeed that human art and skill

Can bind the sunbeam to its will.

The Daguerreotype

By Adele Kenny

Reprinted with the kind permission of The Antiquer.

Copyright © 2003. All rights reserved.

As early as the fourth century B.C., Chinese scholars wrote about the camera obscura: if a small hole is pierced in a piece of paper that is placed in the window of a dark room, an image of the outdoor view will be projected, inverted, onto the opposite wall. During the early 1800s, various individuals experimented with this concept and attempted to fix projected images on light-sensitive materials. In England, Thomas Wedgwood discovered in 1802 that silver salts would render paper or leather sensitive to light, and a few decades later, another Englishman, Henry Fox Talbot, produced a paper soaked in table salt and silver nitrate then washed in potassium iodide that became a negative from which he could make limitless positives by placing additional sensitized papers in contact with the negative and exposing them to light. In 1829, Frenchmen Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre and Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce collaborated in carrying out image-making experiments with the goal of creating an image from life through a reaction to light. After Niépce’s death in 1833, Daguerre continued to experiment, and on August 19, 1839, his photographic process was made public via the French government – an announcement that literally changed the world.

Named for its creator, the daguerreotype was made through a direct-positive process that created a detailed image on a sheet of copper that was plated with a thin coating of silver without the use of a negative. The silver plated copper plate was first cleaned until its surface resembled a mirror. The plate was then sensitized in a closed box over iodine until it took on a yellowish-rose color. The plate was next placed in a lightproof holder and transferred to the camera where a lens cap was removed and the exposure was started. After being exposed to light, the plate was developed over mercury until an image appeared. The image was fixed by immersion in a solution of sodium thiosulfate or salt before final toning with gold chloride. The earliest daguerreotypes required long exposure times that ranged from three to fifteen minutes – times quickly reduced through adjustments to the sensitization process and lens improvements.

Because daguerreotypes were produced inside the camera, they are unique, one-of-a-kind, images. Copies were only possible through photographing an original image or through lithography or engraving and, often, daguerreotype portraits of important persons were reproduced by the latter means for publication in printed materials. Daguerreotypes are easily distinguished from other forms of pioneer, one-of-a-kind photographs like ambrotypes and tintypes because of their mirror-like appearance. Ambrotypes, produced slight later than daguerreotypes were less expensive to make by securing faint images on the backs of small glass plates. Although they looked like negatives, they were not, and each required a backing of black varnish, black-painted glass, or black fabric to be seen clearly. Tintypes were the last of the one-of-a kind early photographs. Like daguerreotypes, tintypes were produced on metal plates rather than on glass like ambrotypes. The metal used was iron, and the term “tintype” is a misnomer of uncertain origin. To make a tintype, a wet collodion process on black or brown enameled plates was used to produce positive images directly on the iron plates. Distinguished by dark surface coloration, tintypes achieved popularity over daguerreotypes and ambrotypes because they were cheaper to produce, less vulnerable to breakage or scratching, and not subject to oxidation. However, they lacked the daguerreotype’s refinement and came to be known as “the poor man’s daguerreotypes.” Made extensively in America, they were largely rejected abroad.

The daguerreotype process was introduced just two years after Victoria acceded to the British throne. Joining other post Industrial Revolution successes, Daguerre’s announcement was concurrent with advancements in various technologies, and photography, even in its infancy, took the western world by storm. Americans, in particular, adopted the process with astonishing enthusiasm. Pioneer American photographers progressed beyond Daguerre’s still life and architectural subjects into portrait photography even before accelerants were developed and, despite specially designed stands that helped the “sitter” remain still, many a stiff neck must have resulted from the long exposure times needed to make the first portrait images. Just prior to Daguerre’s announcement, he met with Samuel F. B. Morse in France where they shared ideas. When Morse returned to the United States, he became involved in image making along with Robert Cornelius of Philadelphia, John Johnson, and Alexander Wolcott (who invented a camera that shortened exposure time). In record time, photographers from all walks of life joined the image-making brigade as specialists and as itinerants (who combined various trades with side professions in daguerreotyping). A satellite industry in making cases to protect the delicate images developed at the same time and became highly competitive.

By 1851, stereographs, or stereo views, were made using the daguerreotype and ambrotype processes. These consisted of two views of the same image taken by cameras placed next to each other. Later, binocular cameras were used to produce images of photographic subjects on single negative plates. When developed, the paired images were viewed stereoscopically in specially designed cases to create a three-dimensional image.

Americans comprised the daguerreian vanguard, and by the mid-1850s, New York City had become the center of photographic activity. Specialist case makers grew in number, but many photographers doubled as case makers and photographic materials and apparatus suppliers. Traveling agents promoted the new industry and, before long, daguerreotypes were being made throughout the country. The Boston Daily Evening Transcript (December, 18, 1850) reported, “…American daguerreotypes are acknowledged to surpass either English or French.” And, in 1853, The Illustrated Family Christian Almanac for the United States contained the following entry, “Everyone is familiar with the daguerreotype, in which not only likenesses of persons, but images of all kinds of objects are transferred from the lens of the camera obscura, and permanently fixed on metallic plates.”

Today’s collectors seek all three pioneer photographic forms, but daguerreotypes are the most sought after. Average daguerreotypes of unidentified persons are the least highly valued and may be purchased for $35-$55. Daguerreotypes were made in a range of sizes; the largest (whole plate) are the most rare and costly. Because daguerreotypes were kept in cases made of die-engraved paper and leather or of plastic composition and novelty materials, they are often sold as case and image units: combined rare cases and rare images command the highest values. Cases and images by Matthew Brady, whose photographs of Civil War battle scenes were the first record of America at war, are among the highest priced, along with extremely rare views of the moon and identifiable places like Niagara Falls. Collectors compete for Civil War soldiers and scenes, portraits of important persons, Afro-Americans, American Indians, occupational portraits (especially those including “tools of the trade”), post mortem images, nudes, images of circus sideshow or deformed individuals, outdoor views, hand tinted images, and stereographs. Also uncommon and pricey are daguerreotype portraits of people holding daguerreotype cases or standing beside a table on which a daguerreotype case was placed.

It is hard to imagine, in today’s digital culture, the extent of the daguerreotype’s impact on the lives of everyday people whose likeness could be recorded for the first time with the accuracy of permanent mirrors. Perhaps these excerpts from a poem entitled, “Lines on a Daguerreotype,” (Boston Daily Evening Transcript, August 7, 1850) sum up the popular sentiment of the time as well as the feelings of twenty-first century collectors:

Delicate pencillings of imprisoned light!

Tracings imprinted with the finest care,

Revealing to the eye an image bright…

…’tis strange, indeed that human art and skill

Can bind the sunbeam to its will.